Our Lady's Exemplarity

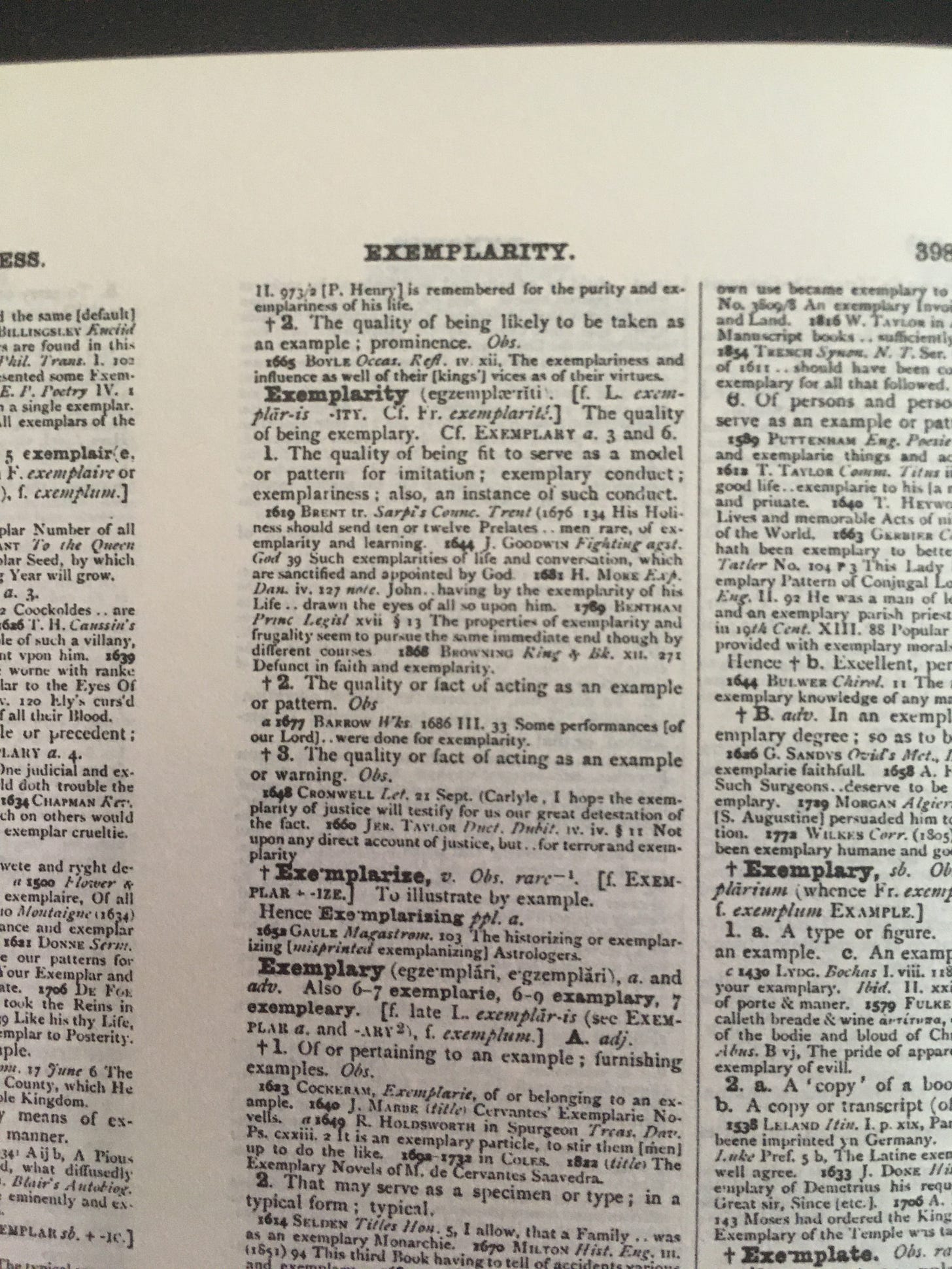

Although the word processing program that’s built in to the substack platform “thinks” otherwise, exemplarity really is an English word (or rather, a Latin-derived word in the English language). The squiggly line that appeared under it when I typed it, however, did lead me to check my faulty memory by using a fairly trustworthy source: my not-quite-antique compact edition (in print!) of the OED. Yes, if the OED editors say it’s an English word, I’m content to assume they are correct.

With that minor doubt removed, I can move on the heart of the matter of today’s post. When I last posted, upwards of two months ago, I made a claim and noted my intent to defend it: “There is no better exemplar of love of learning than the Virgin Mary, the preeminent Veiled Lady to whom this newsletter is dedicated and to whom its title chiefly refers. Explaining why I make this assertion will take a few posts, which won’t exhaust all the possibilities for illuminating the topic, but hopefully will sketch out the main merits of my claim.” In the context of all that could possibly be said about Our Lady, of course, her exemplarity is far too big a topic for a book, much less a short commentary such as this one. The field is considerably narrower, intentionally: I only wish to explain and prove that she is the best exemplar of love of learning. Or at least make a start on explaining and proving my claim.

Now, our human ideas about the topic of learning, as noted in my prior post, are subject to all sorts of distortions and corruptions. It’s no secret, for example, that erudite folk, if they don’t guard themselves against it, can become more enamored of their reputations for being experts in their fields, than they are devoted to the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth — including the humbling truth of how limited their own knowledge of their fields actually may be.

In many respects, however, the larger problem is that people don’t want to believe many things that are true. Plenty of mundane examples come to mind: the youngster (or not-quite-grown-up oldster) who refuses to believe that various ordinary limitations on mere mortals don’t apply to them, such as the need to consider carefully before spending money, the need to choose companions and intimate friends carefully, and so on. I could be more explicit, but I don’t see a need. Everyone who gives it just a little thought can come up with half a dozen examples of someone they know (perhaps the person in the mirror) who fails, now and then, or a lot of the time, to live realistically, accepting real-world truths that limit the fulfillment of our desires, be those desires wholesome, wise, or not. The point here is simply that all human beings resist receiving, accepting, and living according to truths that run counter to what they would prefer the truth to be. That being the case, there are plenty of people who merely appear to love learning; that is, they love learning until and only until a truth smacks them in the face that they don’t want to admit is true. A pointed fictional illustration of this principle is the ultimately damned character Lawrence Wentworth from Charles Williams’ novel Descent into Hell, who betrays his own calling as a scholar of history because … okay, I’ll stop there. Read the book. He’s one of many fictional examples of knuckle-headed men of great learning who in the final analysis loved themselves and their own desires more than they loved … learning, which properly understood and properly undertaken, in all humility, must lead to truth, not some other goal, however flattering to one’s vanity and pride that other goal may be. Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, the scholar who wanted to be God, illustrates the point, and he is certainly a primary literary forebear of countless other Faustian fools, not only in fiction, but alas, in real life.

Our Lady, mother Our Lord Jesus Christ, stands in stark contrast to this phenomenon of confusing love of self with love of learning. Among the many things that Our Lady, the mother of God, had to accept is the profound suffering she would undergo in living out the consequences of her fiat. Unlike Eve, her distant ancestor, she was visited by a good angel, who announced to her the unprecedented news that she was to be the virgin mother of God. She didn’t hesitate to recognize the trustworthiness of the messenger, and she didn’t hesitate to accept what she was called to do. Again, her situation sharply contrasts with that of Eve, who received an evil angelic being, failed to recognize his untrustworthiness, and allowed herself to be seduced/persuaded into imagining a role for herself as God-like arbiter of good and evil — a role to be obtained (so she thought) by disobeying her Creator and spurning reality itself.

The Virgin Mary’s fiat is closely aligned with her Magnificat. That is, in saying both “be it done to me according to thy word,” and subsequently “my soul doth magnify the Lord,” she is declaring not only her faith in God but also her intention to see His glory in all that he is doing, including bringing honor to her perpetually (“from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed”). In short, all the unprecedented things she is beginning to learn, in those very early days of the Lord’s Incarnation in her virginal womb, is referred back to her love of Him — her love of the truth, and her love of learning, ever more deeply, the truth.

Not long after Our Lord was born, of course, she presented her infant Son in the temple, and heard from Simeon, “thy own soul a sword shall pierce,” and indeed, Our Lady’s suffering is beyond compare. Not only is it beyond compare, however, it never stopped her from embracing the truth, in all its dimensions. Unlike St. Peter, she never resisted the truth of her Son’s suffering on the cross, and she never abandoned Him as he was suffering and dying. She is indeed the very best exemplar of love of learning, understood in this absolute context. To say we love learning, and love the truth, while resisting or shirking or denying some aspect of it that displeases, mortifies, or frightens us, is to fall short, as we all inevitably do, of the model of love of learning given to us by the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Ave Maria, gratia plena, Dominus tecum. Benedicta tu, in mulieribus, et Benedictus Fructus ventris tui, Jesus. Sancta Maria, mater Dei, ora pro nobis peccatoribus, nunc et in hora mortis nostrae. Amen.

Will you compose more in this series?